Atlanta author shares emotional insights on identity

Posted by Elena del Valle on February 23, 2022

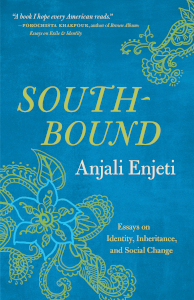

Southbound

Photos: University of Georgia Press for cover, Mira Sydow for author photo

Anjali Enjeti, who teaches creative writing at Reinhardt University, believes her move from Michigan in 1984 to Tennessee forced her to experience a new environment where she was racially targeted. In Southbound Essays on Identity, Inheritance, and Social Change (University of Georgia Press,$24.95) she describes the effects of the move on her life, on her own self-perception and as the source of much anger.

When asked if there is a way to right wrongs without discriminating and or committing new wrongs she replied, by email via her publisher, “I suppose we’d have to define what we mean by discrimination. Is undoing some of the legacy of slavery or Jim Crow through affirmative action in college admissions discrimination? Is providing grants to minority owned businesses discrimination? Of course not. Attempts to level the playing field and address the ways that systems have historically marginalized various groups are not discrimination, and they are certainly not committing new wrongs.

What’s that saying? When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality feels like discrimination. We can’t right wrongs unless we go deep into history, understand systems of power, and how they benefit, and explore how meaningful reparations can make people whole again. For people who are privileged, I suppose this could look like committing new wrong, but it’s really not.”

“The problem is that the people who are deciding how to right wrongs are often very privileged folks who have never been harmed by these wrongs to begin with,” she said when asked to define the boundaries to address such changes and who gets to decide. “In an ideal world, the communities who have endured the harm will get to decide how we can address the harm. Communities most affected by police violence, for example, should determine whether their city’s police force should be defunded and what community programs should be implemented to replace the police.”

When asked who should shoulder the burdens, financial and otherwise, of righting those wrongs she said, “In some sense, we all should. We all pay taxes, and our taxes should absolutely be going toward righting wrongs. Our governments and agencies need to center those most harmed. But more generally speaking, people with privilege need to get more involved in writing the wrongs. We need to be supporting mutual aid organizations by amplifying their work and donating funds. We need to quit self-segregating and push for programs that help everyone.”

When asked if “articles must be judged for bias on an individual basis” as she states in her book how she would judge her book for bias she replied, “Because I wrote Southbound, it’s difficult for me to judge it for bias – that’s a job better left to readers! But I did hire an authenticity editor for the book. She went through the manuscript with a fine tooth comb to help ensure that my words didn’t harm others.

We are all biased as human beings – we can’t not be. And of course this bias is reflected in our writing. But we need to be cognizant of the fact that our internalized biases in writing can harm others, and minimize this harm as much as possible.”

In relation to the anger she described feeling in her book and the acceptable limits of anger she said, “Well if we’re talking strictly about anger, not, say, harassment, bullying or other kinds of violence, then I don’t believe there are or should be acceptable limits to anger. But I suppose this is because I don’t see anger as a failing or an inherently bad thing to begin with – I find it crucial to justice work and the push to make our world more humane. Ultimately, anger is the engine for advocacy.

At this very moment, scientists, and doctors from all over the world are railing against governments and public health bodies that have failed to do their due diligence to slow the spread of COVID and take care of our most vulnerable people. Their critiques have been harsh, angry, enraged. We’re talking about the value of human life. So I don’t find this anger unacceptable in any way – it’s being deployed to reduce and end suffering.

And on an individual level, anger is such an important emotional release. I’m angry when my children are mistreated by others. I’m angry about my chronic pain. I’m angry about a lot of things. This kind of anger is healthy and important and helps me cope. It also helps me grow. And after it’s released, I have far more space in my heart and head for joy.”

Anjali Enjeti, author, Southbound

When asked what prompted her to write the book she said, “I’ve been doing progressive social change work for most of my adult life. Even pre-2016, I never had any delusions about how this country worked, who it benefited, and who it disenfranchised, incarcerated, killed, or deported. But Trump’s election in 2016 shook me to my core. And then I learned something that shocked me – that Asian American and Pacific Islanders have one of the lowest voter turnouts among any racial group. So I switched into electoral organizing, and began volunteering for campaigns. It was different kind of work for me, and I was doing this work in my forties, a decade when my perspective on the world began gradually shifting. A space in my mind began to open up for this book to come through.”

From idea to publication it took five years for the 230-page softcover book to be published in 2021. About 20 percent of the essays in the collection had previously been published.

She added, “And my ideas for new essays were seeds that had been planted in my mind years earlier, so by the time I sold the book proposal to UGA Press and sat down to write them, the essays came easily to me.”

Regarding the primary target audience for the book she said, “I wrote this book for all kinds of people, including southerners, and people of multi-ethnic or multi-racial identity. But I primarily wrote this book for people who think about social change, and activism, and for those whose identities and communities shape how they hope to get involved in social change work. I wanted to write about what identity can do out in the world, how it can build coalitions within and between communities, and this is the audience I was hoping would find the book.”

When asked for her definition of ethnicity she said, “Ethnicity is a cultural group irrespective of race.” To the idea that some people dislike or take offense to labels that others consider essential to their identity and when it may be acceptable to describe someone as brown, black, white, white passing, she said, “This is an excellent question and it’s also a tough one to answer. Terminology to describe race or ethnicity is ever-evolving. It changes every few years, and with each generation. But I think the most important thing to understand is that communities are not monoliths. One person in a community might take offence to an identifier another member in that same community connects with.

I personally identify as mixed race and brown, but not all South Asians or Indians identify as “brown.” I also identify as a minority – a term that many non-white people reject, and I completely understand why. But I feel empowered by it. “Minority” has historically been used to define members of an ethnic or racial group that is smaller in number, but now minorities are becoming the majority, and I love the irony of using the term today where whites are now becoming the minority.

We need to be flexible when we discuss language of identity. It is not one-size-fits-all. We need to listen to individuals and respect how they want to be addressed.”