Higher efficiency, cheap foreign labor, profit driven employers lead to domestic job losses

Posted by Elena del Valle on May 30, 2012

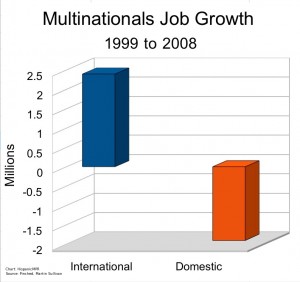

Multinationals Job Domestic and International Growth 1999-2008 – click to enlarge

It used to be that the pace of innovation kept employment numbers strong in the United States. As some jobs became obsolete and migrated overseas workplace evolution and new technologies resulted in the creation of new jobs that outpaced the losses. Over time, as innovation slowed, more jobs migrated out of the country than were created and access to cheap international human resources and continuous corporate desires for profit continue to fuel the trend with few or no tax consequences to stem the job losses.

In 2007 multinational companies employed 19 percent of the private sector workforce, earned 25 percent of private sector profits and paid 25 percent of private sector wages. For all their impressive presence and efficiency these companies were not noteworthy on the job creation side, according to a 2010 McKinsey Global Institute report cited in Pinched.

In the last 20 years, multinationals have been responsible for 41 percent of labor productivity in the United States corresponding to only 11 percent growth of employment in the private sector. The production cycle many relied on meant initial production in wealthy nations with abundant innovation that eventually moved to countries with lower labor costs. In the United States, hardware manufacturing and data processing jobs shrunk when both were expected to grow.

At the same time, and especially during the Great Recession, companies pushed for greater efficiency, driving staff to work longer hours and accomplish more with less. Some developed new processes and methodologies and others accomplished their efficiency goals by squeezing more hours and labor out of employees who feared for their jobs and way of life in a declining economy. These strategies have led to greater stock value for publicly traded companies and higher profitability for many companies overall at the expense of jobs lost that will likely never be recovered. Fewer jobs lead to a slower economy with consumers holding back and focusing on savings. This is especially true when prospective employees are trapped where they are living due to the lingering housing bubble.

An example of the trend is that between 1999 and 2008 multinationals in the United States cut back domestic employment by 1.9 million while boosting foreign employment by 2.4 million, according to economist Martin Sullivan (see Pinched and U.S. Multinationals Moving Jobs to Low-Tax, Low-Wage Countries at Tax.com). At the same time, the figures that reflect a domestic decrease in jobs do not appear to include loss of revenue domestically for individuals who suffered salary and benefits cuts by their multinational employers.